Why not voting means different things in Tehran and New York City

Why did less than 25% turnout in last month's elections?

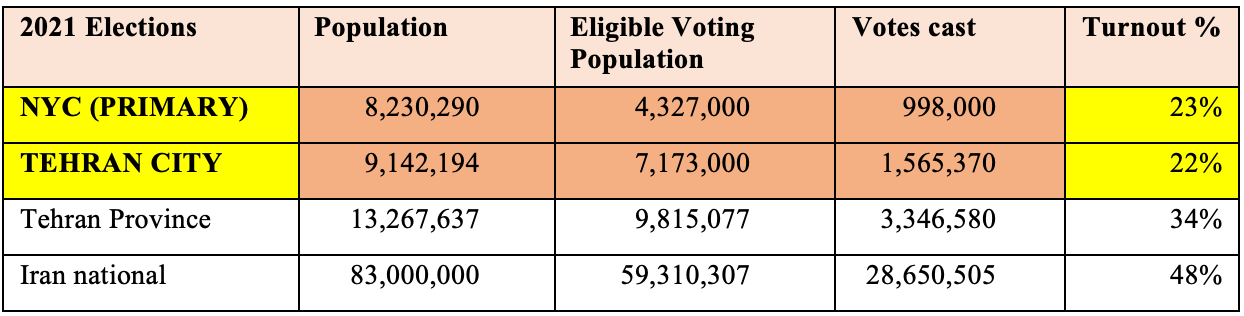

Last month my two hometowns held local elections. New Yorkers voted in closed primaries for a range of offices with the mayor’s office at the top of the ballot; Tehranis voted for president and other national offices as well as 21 at-large city council seats (Iranian Mayors are appointed). In spite of the fact that almost every commentator and pundit in both countries insisted these were very consequential elections, less than a quarter of the eligible voting population turned out to vote for both of them. (In the chart I have included the regional and national figures for Iran to illustrate that Tehran City turnout was exceptionally low.)

Tehran’s eligible voting population is considerably larger than NYC’s. (In NYC primaries, only the 4.4 million registered as Democrats or Republicans were eligible to vote, which leaves out the over one million individuals registered as independents or for small third parties. A total of about 5.6 million registered voters are eligible to vote in the general election. By contrast, in Iran, voters are not required to register.) While the turnout percentages are highly similar, I would argue that this low turnout has highly different implications about the legitimacy of the political systems.

Turnout in most Iranian cities over the last four decades has averaged between 50 and 60%, although Tehran’s average has generally been lower. Voting for local government in Iran is almost always held simultaneously with national offices, which tends to boost turnouts. While in the past some may not have voted because they objected to the Iranian regime’s heavy-handed manipulation of the electoral process (chiefly through the disqualification of candidates and parties), many have argued that voting for the least pro-regime slate of technocrats was the only feasible way of signaling their dissatisfaction.

By contrast, the turnout, however low, in NYC was higher than comparable recent elections. Democratic primaries in the last three citywide and mayoral races in New York in 2009, 2013, and 2017 was a dismal 11%, 17%, and 15% respectively. It also converges with the low citywide election turnout which has been steadily declining from 60% in 1989 down to around a quarter over the last decade. (Nationwide in the US, local elections nationwide draw about 15-35% of the electorate.)

But there are at least two reasons why we might have expected turnout for the primary in NYC to be higher. Because NYC is a “deep blue” city – meaning that the vast majority (70%) of registered voters are Democrats – the winner of the Democratic primaries will likely determine the outcome of the general election in November. Likewise, there was a discernible ideological divide among candidates in the most important of the races. In other words, for a concerned NY voter, this was the stage at which to get involved. Yet, as in Tehran, more than three quarters of voters abstained.

In spite of this symmetry, my own experience suggests that the meaning of nonvoters differs in the two systems because elections have very different functions and very different deficiencies in the two societies. The US is a capitalist liberal democracy. Here elections function fundamentally as a means for citizens to consent to be governed by their representatives, that is, to authorize the government. While it may lack high levels of participation by a highly informed electorate that closely evaluates policy agendas and politicians’ performance, nonetheless this core dynamic distinguishes its electoral system sharply from that of Iran.

Iran is a non-liberal Islamist autocracy, as defined by political theorists, because no election can oust the chief executive, the Supreme Leader or the key institutions under his control. Elections are used as an instrument of top-down nondemocratic rule – a quite effective one. As I’ll lay out below, similar motivations may drive individuals to vote, but nonvoters in the two systems generally mean quite different things. Let’s look at the two cases before drawing some general conclusions. In exploring the profile and motivations of nonvoters in the US I can draw on some polling data, but there is almost nothing available about Iran’s nonvoters. Nonetheless, I can make some extrapolations based on a few studies of past voting trends, the nature of the political system as a whole, and personal experience.

Faced with the chance to shape their city’s government for a decade or two…most New Yorkers stayed home

In NYC, for months news commentators reminded us repeatedly that the 2021 primary election was an unprecedented opportunity to shape city governance for decades to come, because, in a city where Democrats win most elections, the Democratic candidate for every major political office was on the ballot, including for the mayor, the comptroller (a financial watchdog), all five borough presidents, all 51 City Councilor seats, and Manhattan district attorney (DA). Some people cast ballots while leaving some races blank, and thus, not-yet official results indicate that for different races turnout was as low as 20% (City Council) and as high as 24% (among Manhattan votes, for the borough’s district attorney). (As of this writing, the NY Board of Elections has exhibited massive incompetence in calculating the exact total tally, but that will have to be the subject of a future post.) Despite extensive, detailed, and months’-long media coverage of the candidates’ positions and quite palpable contrasts in the ideological orientations of the candidates, a huge swath of New Yorkers did not care enough to vote.

It is often said low turnouts can be a result of the absence of a clear contrast between candidates’ positions. Yet many of the candidates tended to identify either as progressive or what I would call moderate. The former were self-styled socialists and advocates for racial identity and racial justice. They wanted to nationalize (“de-commodify”) housing and land markets, redefine local public policy through a race-based lens, or both. They decried many public institutions such as the police and the current education curriculum as racist, and/or the capitalist system as unjust. The latter emphasized different priorities; they warned of the need to combat the dangerous rise in crime and disorder which threatens to reverse a three-decade drop in crime rates that brought NYC back from the brink of disaster; they also defended greater market-led housing construction to ease the affordable housing crisis across the city. Moderates also stressed the need to get back to the basics of nuts-and-bolts management of the city’s creaking infrastructure systems that are the backbone of the city’s economy – notably the subways – as well as addressing the trash piling up on the streets, degrading the urban environment for poor and rich alike.

The Manhattan DA race pitted the first Iranian American woman running for senior elected office in NY against seven others. This race, in my view, is highly consequential at this historical moment of rising crime and disorder, given its critical role in determining how and which crimes are prosecuted; given marginally higher turnout, it seems that only a few New Yorkers agreed. (I voted for Farhadian Weinstein because of her stellar record more than her ethnicity; she lost to the progressive candidate.) Nonetheless, I would not have expected less than 75% of the electorate to feel that making a choice wasn’t worth the time.

As a voter, I cannot help but feel that widespread apathy, indifference, or ignorance about politics – documented by the most in-depth study of nonvoters in the US - will in the long run threaten the individual civil freedoms that form the foundation of our democratic culture. But I will admit I remain skeptical about the effectiveness of elections as a way of controlling politicians and shaping government policies. At the same time,I think that nonvoters in New York have to be interpreted as giving tacit consent to the political system and the choices on offer. This is different in Tehran and other Iranian cities.

Failing to vote in Tehran: protest or apathy?

The available data does not allow me to separate out the number of voters casting ballots specifically for city local versus for national offices in Tehran. Data for voting in Iran’s 1,400 city council and 37,000 village council elections were bundled with votes for national offices. According to one Iran-based polling expert, interest in local elections outpaced interest in the presidential election, reversing a longstanding trend, but the data do not permit me to confirm this. Indeed, abstention from the local race for city council could have been even higher than the reported 78% overall.

In the few months leading up to the elections on June 17th, Iranians had a chance to hear about a range of political platforms from would-be candidates for national office, including some unprecedentedly bold campaign platforms aspiring to liberalize the political system. Nonetheless, many supporters of opening the political system were skeptical of the value of voting at all, observing that the regime was brazenly arranging the field of candidates to ensure the victory of their favored candidates. As I explained in a previous post, when all of the reformist candidates for national office were barred from running, the umbrella group of reformist parties (jebhe-e eslahat) refused to endorse a candidate for the presidency. But they did advance a list of 21 candidates for the Tehran City Council (top image) with the slogan “in defense of republicanism (jumhuriat) and the people’s choice,” a mild if clear contrast with the slogans of the regime’s hardline candidates, who emphasized the keyword “revolutionary” (bottom image) and placed the regime’s handpicked candidate for presidency at the top of the poster. (Other contrasts included the less orthodox dress of a few of the women on the republicanism slate, as well as the latter’s absence of clerics.)

Despite this contrast, voters were not presented with specifically local platforms or programs by these competing party slates to help them make a choice specifically related to local issues. The track record of the few incumbents on the list on the outgoing council would have provided a useful indication of their likely future priorities, but only a small minority of Tehranis who were local-government wonks would have been in a position to make those judgements. And outside of those few, the best voters could do was to extrapolate from the political affiliation of local candidates what general political orientation they might adopt, but what specifically local policies and priorities these groups might pursue was at best vague. The reformist umbrella group published a 30-page bulletin with almost 190 policies, but it did not include an urban agenda for local government. (It did reference the need to address the system of taxation for land and housing, but that system is set by national legislation.) I did not come across any serious discussion, either in print or social media, evaluating incumbents in ways that could help voters decide between them. High-quality journalism has covered issues such as an innovative initiative to increase transparency in the municipalities’ budgets and contracts, as well as controversies over whether Tehran should permit greater density or encourage private or government housing construction, but these topics did not feature in campaign slogans or published platforms.

Since at least the mid-2000s, when reformists newspapers were closed down, pro-regime candidates have had access to national television and radio, while reformists advocating political liberalization and democratization have not. Reformist candidates therefore took to social media to spread their message, with some success. Over 15,000 people listened to a virtual town hall meeting led by a leading reformist candidate Mostafa Tajzadeh on Clubhouse, a social media platform booming in the Middle East (and in many authoritarian countries). But everyone knew that the regime’s Guardian Council would disqualify these candidates, and many of their supporters surely decided not to vote for this reason.

We can estimate that around 20% of Iranians are apathetic, ignorant, or indifferent about politics, and so will never vote even in a national election. I reach this estimate from looking at the highest turnouts of around 70-80% in the presidential elections since 1979, and others have agreed. Local government elections have never exceeded 65%, suggesting at least 30% are hardcore nonvoters. This leaves about 45% of the electorate’s failure to vote in 2021 unexplained. Such a low turnout is not unprecedented; in the second council elections in 2003, turnout in Tehran was probably below 20%. Then, it was a reflection of the urban middle-class disappointment in what was widely viewed as the poor performance of the reformist city council that they had won in 1999. This year, it appears to be because disqualifications were even higher in this election. There were differences between the “republicanist” slate and the “pro-regime” slate that I would have perhaps found meaningful, but there were no recognizably democratically minded reformists willing to push the envelope, at least at the city level. Probably for this reason, voting held little attraction for many of the usual pro-reformist voters in the capital city. As a result, the hardline faction swept the entire city council. Its first task will be to select a mayor from its own camp.

If disqualifications drove low turnout, it is possible to imagine that abstention from voting reflected a mass protest. Indeed, the number of ballots reported invalid or spoilt (bateleh)—most likely spoiled by the people who cast them, as a form of protest—jumped from the 1-3% range over the preceding four decades to 13% for all posts countrywide this year. In Tehran municipality, the number of invalid or spoilt ballots was an astounding 26% of all votes cast (413,920 out of 1,151,450 total votes cast in the city).

However, consistently high turnouts over the past forty years would seem to suggest that a significant number of Iranians do not find the present Islamist system “illegitimate” and thus intolerable. But I must emphasize that here I am using legitimacy in the realist or thin sense of legitimacy (which I take from Max Weber’s quite Nietzschean-inspired political realism), in which a belief in legitimacy of a political system reflects merely the ability of a ruling regime to generate a minimum of compliance and obedience. This is to be contrasted with the strong or thick sense of legitimacy, expressing the consent of freely deliberating individuals within the cultural context of widespread acceptance of civil and political liberties, permitting the constant scrutiny of a free press, robust competition among opposition political parties, and an independent judiciary – all features sadly absent in Iran. Even for dissidents living in Iran, such compliance can be the result of the lack of feasible alternatives, so thin legitimacy is the most that can be hoped for in Iran.

Another reason it is difficult to know if the drop-off is a protest vote is because we don’t have good information about which of the three political groupings – fundamentalists (usulgara), technocrats (kargozaran) or reformists (eslahtalab) – nonvoters identify with most closely. Nonetheless, the decline in turnout is one indication that at least some of the drop-off was a protest vote. Given the fact that people tend to vote for slates as a whole, we can compare the total number of votes received by each slate as a measure of their popular support. In 2017 the total votes cast for the top 21 vote-getters, who then comprised the council (dominated by moderates together with a few reformists), was 26 million. This year, the top 21 vote-getters were all from the fundamentalist or hardline pro-regime slate (pictured above bottom) and received a total of only 6.5 million votes. The top vote-getter this year, hardline Mehdi Chamran (who was also the top vote-getter in 2003), received 486,000 votes, less than a third of the over 1.7 million who voted for the moderate who took the top slot in 2017. (In Iran’s municipalities, the candidate receiving the highest number of votes automatically becomes the head [rais] of the city council; although selected differently, the rais plays an equivalent leadership role to the NYC Council Speaker.)

A third reason turns on its head the conventional assumption that turnout represents in some way a collective will. Given that the current election demonstrates that people can stay away without suffering obvious forms of repercussions, Iran’s achievement of 60-70 percent average turnout rates over four decades is impressive. But what does it mean? Many people erroneously project ideal liberal democratic assumptions onto the Iran context and assume that turnout represents an indicator of an independently formed “public opinion,” which then shapes government. In reality, it is much more plausible to see the turnout in the Iranian case as the dependent variable, that is to say, it is more accurately viewed as a numerical indicator of the political elite’s success or failure in compelling the electorate to vote. From this perspective, the drop in turnout in 2021 represents only the regime’s (perhaps temporary) failure to manipulate much of the population into participating in what is a collective ritual empty of political consequence.

Taken together, the data we have reviewed indicate at least three things. Hardline pro-regime parties have a ceiling of support in the capital city at around 500-600k votes or about 15% of the electorate. Hardliners are outnumbered by supporters of the reformists in Tehran by a factor of 3 or 4, so if more supporters of the reformists had participated, they would likely have blocked the fundamentalist slate. But it’s also the case that the electoral behavior of pro-reformists voters can change unexpectedly, as in the big drops in 2003 and again this year. Mehrzad Boroujerdi, a leading expert on Iranian politics, refers to their behavior as “emotional voting” in which voters basically sulk in reaction to what they perceive to be an even more manipulated election than the kind that they have become used to over the last four decades.

Why nonvoters mean different things in NY and Tehran: consent and diversity

So given these starkly contrasting contexts – a constitutionally free liberal democracy versus a closed autocratic system of Islamist governance – how should we understand similarly low turnout in difference in the two cities?

Two fundamental differences are worth highlighting, one having to do with diversity of opinions, the other with consent. In NY, as in all open societies, elections reflect the diverse preferences and values of the people coalescing around shifting majorities; elections are a mechanism for reconciling conflicting interests peacefully; and, most fundamentally, voting protects liberty simply by restraining officials by means of popular election and sanction (being voted out). In such a system, nonvoters abstain because they are indifferent to the outcome; ultimately this can be taken to express tacit consent both to the procedural system and whatever specific outcome emerges.

In Iran, as in former communist and other closed countries before it, elections are by contrast intended to demonstrate the unity, not the diversity of the people. Elections are, in fact, referendums on the legitimacy of the regime. (The Supreme Leader in Iran asserted this unequivocally just before voting began, going so far as to say that any spoiling of ballots is a religious sin, thereby fusing apostasy with treason.) As my colleague Columbia University political theorist Nadia Urbanati puts it, under populist regimes, elections don’t create the majority but reveal it. Authoritarian elections thus are basically referendums on the political system as a whole. A study of voting under Soviet communism observed about the purpose of such elections: “the voter is periodically reminded by means of this mass loyalty test and exercise in assent that there is no alternative to the Communist party and its regime, and that dissent is not permitted.” In fact, recalling the thin notion of legitimacy, it is not important that everyone believes in the results of an election, only that they believe that the regime can stage an election. This chilling calculus was echoed by a political prisoner in Iran who recalled asking her interrogator: “Do you really think people will believe these false and forced confessions?” To which he replied: “It’s not important that they don’t believe [your confession]. What’s important is that they believe we can obtain the false confession.”

Consequently, I think it is fair to argue that under nonliberal and undemocratic political systems, not voting (leaving aside the truly indifferent) can be interpreted as a protest vote unless proved otherwise. By contrast, under liberal democracies, not voting should be assumed to reflect tacit consent unless the opposite can be proved. In democracies, one has a real choice not to vote. In other words, abstaining in a democracy might weaken the mandate given to politicians but it does not necessarily weaken legitimacy of the political system as a whole. By contrast, when electoral competition is so restricted and manipulated that the voter cannot have their point of view represented in any meaningful way, the individual is in a sense forced not to vote, assuming that voting means expressing one’s true preference. (Of course, even in a democracy one may feel that one’s choices are constrained, if one’s top choice is not successful in gaining a slot on the ballot, but the key issue is there is no legal barrier facing a party being so represented.)

Notwithstanding all their differences and their respective deficiencies, the two systems held elections with results that their respective populations have accepted. As of this writing, Eric Adams (a moderate to judge by his pronouncements) prevailed in New York’s Democratic mayoral primary, making him the likely winner of the general election in November. In Tehran, discussions are beginning within the new city council about who the next mayor will be, which will be decided by the new city council whose term will begin in September.

It is often said that the choice of mayor, city council, and other local offices, is – or ideally should be – a reflection of an answer to the question of what kind of city the society or the powers that be desire. In the next newsletter, I will explore to what extent the results of local elections, whether in NY or in Tehran, can shape the future evolution of the city.

Super interesting Kian. Thank you for sharing that. When I talk to Americans who don’t vote, the most common response I have heard is that their one vote won’t make any difference with regard to the outcome. It just doesn’t matter. So if it is super easy one might still vote, but if that is the underpying beleif AND one does not have a car to get to the polls or the lines are long, or any other challenge presents itself, then people don’t vote.

In Argentina, where I lived for 15 years, every resident of voting age required by law to vote and people can face fines if they do not. Voting is held on a Sunday and almost all businesses are required to be closed that day. Of course Americans defense of individual rights prohibits us fro even thinking about mandatory voting, but it is amazing to see how engaged the entire public is in electing their leaders.

Kudos to Kian for his provocative argument: that the apparently similar phenomenon of low turnout in Tehran and NYC reflects quite different, even opposite, voters' motivations. I find his interpretation of the reason for low turnout in Tehran highly persuasive. However, I agree with Sibylle Johner that low turnout in NYC (and, more generally, U.S. elections) is not simply an indication of tacit consent/authorization of the incumbent government/political system, although I assume she'd agree that this is part of the explanation. Although I also agree with her claim the importance of anger and disillusionment, I'd add several other reasons for low turnout: ignorance, including (for some) ignorance that an election is even taking place, as well as ignorance about the need to register to be eligible to vote, the location of one's polling station, the hours when one can vote, etc. Another reason, linked to the preceding: multiple procedures that reduce the likelihood of voting, including the need to register to vote, the limited hours when one can vote, limited number of polling stations, the fact that elections in the U.S. are held on a working day (Tuesday) rather than on a holiday--Sunday--as is the case in most liberal democracies, the fact that in many (most?) states former felons are ineligible to vote, etc. A third reason, related to the second: incumbent legislators intentionally restricting voting to increase their chance of re-election, i.e., voter suppression: requiring a government-issued photo ID, reducing the number of polling stations, limiting early voting, etc. In brief, non-voters abstain because of (1) tacit consent/satisfaction with the status quo [Kian's explanation), (2) disillusionment/anger with the choices offered or the entire political system [Sibylle's explanation], and (3) voter suppression, broadly defined [MK's suggestion]. Although all three are doubtless influential, I suspect that nos. 2 and 3 outweigh no. 1.