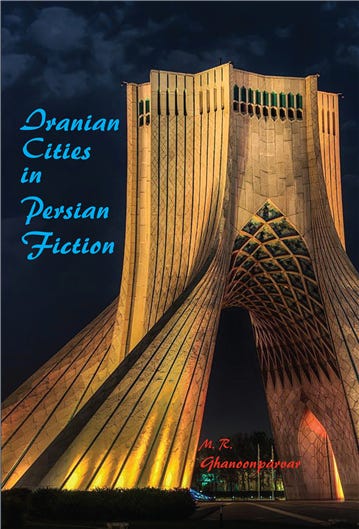

My book review of: Iranian Cities and Persian Fiction by M. R. Ghanoonparvar

Final version to be published in the journal Iranian Studies

In this original and engaging book, M. R. Ghanoonparvar seeks to “understand how creative artists have shown cities in the mirror of their fiction.” The main part of the book consists of seven chapters, each devoted to a single city in Iran. Each chapter begins with the author’s personal reminiscences from his youth, then moves to a discussion of a range of fiction published from the early twentieth century through to the present. Most of the works discussed are novels and short stories by well-known writers such as Sadeq Hedayat, Jalal Ale-Ahmad, Ebrahim Golestan, Goli Taraghi, Moniro Ravanipour, and Sharnush Parsipour, but a few of the works considered are poems and films, and lesser-known authors such as A. M. Afghani from Kermanshah, Asghar Abdollahi from Abadan, appear as well.

Each city, we learn, has a unique identity that is evident in the selected texts. Most of these identities are relatively bleak. A majority of the almost thirty works in the chapter on Tehran portray the capital city as gloomy, dismal, and chaotic, beset by class contradictions such as the huge gap (captured for Ghanoonparvar in a 1969 poem by Esmail Khoi) between the impoverished southern neighborhoods and the wealthy northern ones. Recent migrants from smaller provincial towns feel alienated and lost. Their dislocation, according to many of the works of the 1970s, give Tehran a lack of “cohesive structure.” For writers such as Nader Ebrahimi and Ebrahim Rahbar, the city is “strange and alienating,” “incomprehensible.” In a 1967 story that became a 1975 film, “Ashghalduni” Gholamhoseyn Sa’edi called the city a “dump”. Only Mahshid Amirshahi’s Suri stories depict Tehran of the 1970s as a pleasant and interesting place, but in later works she describes a “city of riots, confusion, filth, fear, killings, death and lawlessness” in the run-up to the 1979 revolution (22). Similarly, a few works produced in the 1980s and 1990s, such as those by Goli Taraghi and Moniro Ravanipour, highlight nostalgia for pleasant and tranquil experiences of the capital city but decry its contemporary circumstances. Such works suggest that historical circumstances of political upheaval and uncertainty, rather than any essential nature, make the city dark. But perhaps not: as a character in Ghazeleh Alizadeh’s 1999 novel Shabha-ye Tehran (The Nights of Tehran), set in the 1960s and 1970s, declares, “Tehran is such an ugly city devoid of personality.” The class revolution that Khoi’s poem called for, according to works like Amirshahi’s Dar Hazar (At Home, 1987), has not improved the city; in fact, it has done the opposite. Further criticism appears in stories by Shahrnush Parsipour, which suggest that Tehran is not welcoming to women. (In the view of a number of the authors, the whole country is patriarchal and often misogynistic, a topic Ghanoonparvar does not take up.)

Almost as intriguing as the assertion that Tehran is a “Schizophrenic City,” is the idea that Ahvaz is the “Forgotten Cosmopolitan City,” and Abadan a site where “East meets West in the concrete jungle.” But some of the other claims are more conventional, even clichéd, and the literature discussed often contradicts these claims. For example, Ghanoonparvar opines that the culture of Shiraz is the “suffering arising from unrequited love” and “unfulfilled yearning," themes commonly attributed to the classical poetic tradition associated with Shiraz. Yet his insightful discussions of several works – such as Hedayat’s Dash Akol, Chubak’s Sang-e Sabur, and Reza Julai’s Shekufeha-ye Annab – belie the benign and even banal conclusion that “Shiraz is remembered for its wine, roses, orange, blossoms, nightingales, beautiful gardens, and great poets'' (106). In fact, many of the stories explore dark and disturbing themes: loneliness, fear, death, murder, “utter hopelessness,” nightmares, bleak experiences of impoverished and cruel childhoods prompting the desire to leave and never return. Nostalgic memories are, we learn, unreal delusions that dissipate in the face of everyday life. A character in Ravanipour’s Shabha-ye Shurangiz “grows tired of the scent of the orange blossoms” much as in a short story by Mandanipour, as Ghanoonparvar observes, “the bitter orange trees are a symbol of Shiraz itself” (104), rendering the title “Shiraz, city of wine, roses, and nightingales” ironic.

In the chapter on Isfahan, we find a similar disconnect between the conventional stereotype and the narrative of the story. The conventional image of a benign city boasting grand historical architecture, art, and alluring public spaces around the famous Zeyenderood River appears largely in the works of outsiders, whereas stories by natives show a different view. Ja’far Modarres Sadeghi’s Ghavkhuni, for example, emphasizes the dark and terrifying marsh outside of Isfahan, which for locals is as much a symbol of the city as the majestic seventeenth-century main square of the Safavids. On the other hand, Ghazaleh Alizadeh’s novel set in Mashhad (Do Manzareh) does not at first focus on the famous shrine which draws the most tourists in Iran, highlighting instead the relationship between a middle-class urban woman and a man from a poor nearby village; still, the identity of Mashhad as a sacred city ends up dominating the story.

Ghanoonparvar assigns to each city a specific and dominant identity, which may oversimplify the complexity but enables him to organize the literature he has included. This allows ample space for readers and future scholars to contest, revise, and develop the interpretations in each chapter. Whether Ghanoonparvar’s overall critical pessimism reflects the negative slant of the writers represented in this volume – most of Iran’s intellectuals have been critical of modernization and the commercial civilization closely associated with modern city life – or whether Iranian culture more broadly harbors a deep anti-urban sensibility is one of the intriguing questions this book raises, though it leaves others to answer it.

In terms of methodology, the introduction notes that this is not a comprehensive study of covering all the available literature covering all possible cities. Ghanoonparvar concedes that the availability of literary works, rather than any typology emerging from the cities’ characteristics, drove the selection of the seven cities. Although this may not satisfy social scientists who might seek a more systematic frame of comparison between cities, it is suitable for a cultural and literary study.

The only criticism I would venture with respect to methodology relates to the absence of an orienting discussion in the introduction of any prior scholarly work or literary criticism in this domain, situating Iranian Cities and Persian Fiction in relation to the large body of scholarship on the city in literature. While sociologists and historians pioneered this domain, cultural critics including Raymond Williams’s The City and the Country (1975) and Marshall Berman’s All That Is Solid Melts into Air (1982) have brought this type of investigation fully into the realm of culture, and the trend continues up to the present, as demonstrated by the multitude of works on virtually every body of modern and pre-modern literature investigating the role of the city and the imagination of urban life as an essential human experience. Reference to such works would have demonstrated the importance of Ghanoonparvar’s own study, as well as situated the work more fully in a comparative context and deepened our understanding of Iranian urban experience. To be fair, Ghanoonparvar usefully references more detailed works of literary criticism in the footnotes, but these mainly refer to discussions of Persian literature, and relegating them to notes forecloses the possibility of fuller engagement; at any rate, broader comparative and theoretical dimensions are not reflected in the main text.

Indeed, several motifs recur throughout the volume which could inspire future studies of the multiple dimensions of modern urban culture in Iran, including other forms of artistic expression and other themes. Perhaps the theme with the most significant implications for the future of Iranian society is the assessment of the commercial culture of modern liberalism and capitalism as the key shaper of city life. The raison d’etre of modern cities is the innovation and economic growth generated by the cross-pollination of ideas generated by individuals and firms living close to one another. To ignore this spontaneously emergent order of the city is to refuse ultimately the creativity and innovation arising from healthy competition of “sweet commerce” which is the necessary if not sufficient condition for the best of modernity: the combination of prosperity and freedom. By contrast, Sadeq Chubak calls the modern city the “unhappy gathering place” (10) of different types of people. Not a single story included by Ghanoonparvar extols the creativity and progress that modern urbanism can bring. Perhaps works not covered in this book embrace these possibilities? Or is this anti-urbanism a clue to the anti-modernism of Iranian culture? (In this regard, I note the omission of Ja’far Shahri, who celebrated all aspects of city life in numerous works on Tehran.)

As far as this reviewer is aware, Iranian Cities and Persian Fiction is the first book in English to illuminate such a question based on Iranian cultural products. It is clearly written and illuminates aspects of city life and urban culture, offering a fresh perspective on well-known works and attention to more obscure ones. The book will interest undergraduate and graduate students of Persian literature as well as comparative studies of the culture of cities. It is thus a welcome addition to a neglected aspect of Persian literature produced in Iran but also to the study of urban life and the culture of cities in Iran in the 20th and 21st centuries.